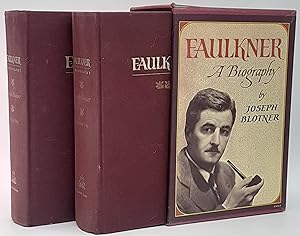

And his first marriage wasn't so hot, but his second, to writer Eleanor Clark, worked out pretty well. He almost went blind in one eye as a young man, and he did attempt suicide (chloroform in a hankie) while an undergraduate at Vanderbilt University, which he chalked up to "ennui," an explanation Blotner basically leaves be. One problem is that the arc of Warren's life - he was born to a middle-class family in Kentucky in 1905, and died respected and prosperous at age 84 - seems so placid and successful. More general readers might need a bit more to keep them turning the pages. Blotner's bio of this eminently accomplished writer is, well, eminently accomplished: meticulously researched, unerringly chronological (without so much as a theme-extracting introduction), voluminous and politely distant - all qualities one looks for in a biography if one is a scholar. Nor does Warren's work inspire the kind of contemporary devotion that his close friend Katherine Anne Porter's does. Yet, unlike William Faulkner, the subject of Blotner's previous biography, the word "genius" is rarely bandied about with regard to his work (although he did receive a MacArthur "genius" grant). Warren was equally prolific and prodigious as a poet, novelist and historian. The tough question is: Where does his work ultimately figure in the fickle, fruited plains of American literature?

Robert Penn Warren may be a quintessential American "man of letters," but after wading through Joseph Blotner's big, redoubtable biography, you can't help but wonder if Warren might have held that title in the same way George Bush was considered a "risumi politician." It's not that Warren wasn't talented, and certainly his name is followed by a dizzying array of honors - he won several Pulitzers (including one for his novel about politics in 1930s Louisiana, "All the King's Men") and Guggenheims, he was a National Book Award winner and the U.S.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)